It is always interesting to theorize about what may happen in the future, philosophize on the topics of anarcho-capitalism or cypherpunk culture and dream of the world in which sound money finally dominates market relations. But if all we did were to indulge in mental exercises all day long, nothing would be done, no progress would take place. Let academics do that, while we, practical individuals, tinker with our knowledge in real-life situations to see what actually works and what does not.

Applied cryptoanarchy is the application of existing knowledge about cryptography in practical tools, such as PGP or bitcoin, in a permissionless manner. In The Bitcoin Business Suite, I described a concept for a business tool that allows for the creation of a circular bitcoin economy—an independent market that operates exclusively online. What is notable about my fairly simple proposition is that its components already exist. We use some of them in our daily lives as stand-alone tools. Bitcoin is our money. Hardware wallets are getting traction. PGP is still the most popular email encryption tool in the world. And businesses like Bull Bitcoin already utilize the OpenTimestamps protocol to timestamp their cryptographic contracts.

In this article, I will demonstrate how to create a cryptographic contract using only two components: PGP and OpenTimestamps. But before that, let us start with some basics.

The Premise

First of all, we must understand what a cryptographic (or crypto) contract is and how it is different from a traditional contract. Let us describe the latter by referencing the writings from the good olden days of Bitcoin.

"This contract, or should we maybe say Contract is quite the term of art, and it means a. an agreement b. reached by willing participants which c. shall be enforced against them."—Mircea Popescu, GPG Contracts

The difference between a handshake agreement and a written contract is that the documented version can be enforced in a court of law provided by the State or in a private arbitration facility. This means that complete strangers may enter into contract knowing that, in case of a breach, enforcement falls under a court's jurisdiction. Although in theory it means that both parties are equal before the court when it comes to litigation, reality, as we all know, begs to differ.

"The attempts mostly end up as a competition of "who has the largest bank account" and therefore can afford the best lawyers, and since this is known at the outset the only real believers in the entire contract-with-enforcement construct are, predictably, the very large corporations."—Mircea Popescu, GPG Contracts

On an individual level, I am a believer in handshake agreements for one simple reason: I do not want to do business with someone who cannot honour a verbal promise. Those handshake deals that actually work out, do so because of a very important component in human relations—trust.

In our close circles, we determine whom we trust or not by observing individuals' actions. It is purely a matter of judgement. But how can we trust a complete stranger? The saviour here is another concept that is as old as humanity itself—reputation.

In daily affairs, we often choose this or that merchant either by suggestion from people we know ("This butcher has the best dry-aged steak, check it out!") or by checking their reputation score on Google or Yelp. This way, we can enter into an agreement with them without needing to sign anything. If the merchandise is satisfactory, we are likely to increase our trust in the vendor and even add to his reputation ("⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Amazing, locally sourced, grass-fed cuts. Highly recommended!").

As we can see, trust and reputation are interdependent. In a startup phase, they may even present a chicken-or-egg problem. With time, one's reputation grows and so does the trust in him. Systems that track reputation scores are called Webs of Trust. We may find a built-in WoT in Uber, AirBNB and Expedia or stand-alone services like Trustpilot. There is no universal protocol for WoT on the Web that anybody can use today, primarily because it all comes down to the problem of digital identity. While numerous tools already exist that could be used in such a system, they remain niche products due to poor user experience.

PGP, for example, is a great tool for a WoT which is why it was chosen for the purposes of identity by the early bitcoin community.

"Since all transactions carry with them counterparty risk (risk of non-payment by one of the parties), it becomes important to keep track of people's reputations and trade histories, so that you can decrease your probability of getting ripped off. And thus, the OTC web of trust is born."—bitcoin-otc.com

Mircea Popescu, in using a PGP-based digital identity, saw its immense potential if only it could be adopted by more individuals and businesses. Thus, he proposed a new type of contract between trading parties: a cryptographic contract. (He calls it a "GPG contract", GPG being a popular implementation of the PGP standard.)

"There’s a spiffy young fellow I’m betting on : the GPG Contract. He’s also a. an agreement b. reached by willing participants. But that’s all."—Mircea Popescu, GPG Contracts

In such a contract, there is no court or other arbitration entity that can resolve an issue, should one arise. It is more akin to a handshake agreement. However, it still possesses qualities of traditional contracts: identities of the signees and their signatures. But, instead of passports and calligraphy, we have cryptographic identities and signatures.

If all we had were reputation, how would that change the way we enter into contracts with each other? Simple: suddenly, we become more careful with whom we deal.

Online identities are obviously a dime a dozen, in fact in the time I took to write this opus I might have made a few million. However, because of GPG they are in fact identities. Add to this the fact that nobody forces you to venture money in a deal with something that’s worth a dime a dozen and suddenly some sense begins to emerge.—Mircea Popescu, GPG Contracts

This is why a WoT is an integral part of a system, in which two pseudonymous or anonymous parties want to do business. To earn trust, you must build a reputation. In some cases, this process can take years of honest work. Destroying one's reputation, on the other hand, requires only a few seconds. It is known.

I will mention that, thanks to bitcoin's multisig capabilities, one-time transactional agreements can be entered into with the help of third-party arbitration, which either can be done by the service provider, as is the case with Hodl Hodl, or opened up to the market, like in Bitrated.

But enough of theory. Let us create our first crypto contract!

The Agreement of the Future

Ingredients

Let us start with a basic agreement, in which Alice wants to engage Bob's web-design services.

The contract's SHA-256 hash is:

8a9f17b09aa5c3baa1bba66ffa0ad3c5e56ecebefac0b14e0b5abffa8b473ef5

The key ingredients in this contract are:

- The contract text

- The hash of the contract text

- Alice and Bob's identities represented by their PGP fingerprints

Signing the Contract

First, Bob verifies that the hash matches the contract text. Any tool that can calculate a SHA-256 hash of a text input can be used (check out this one). This step is important because hash functions are a one-way road: a single-letter change in the text will result in a totally different hash.

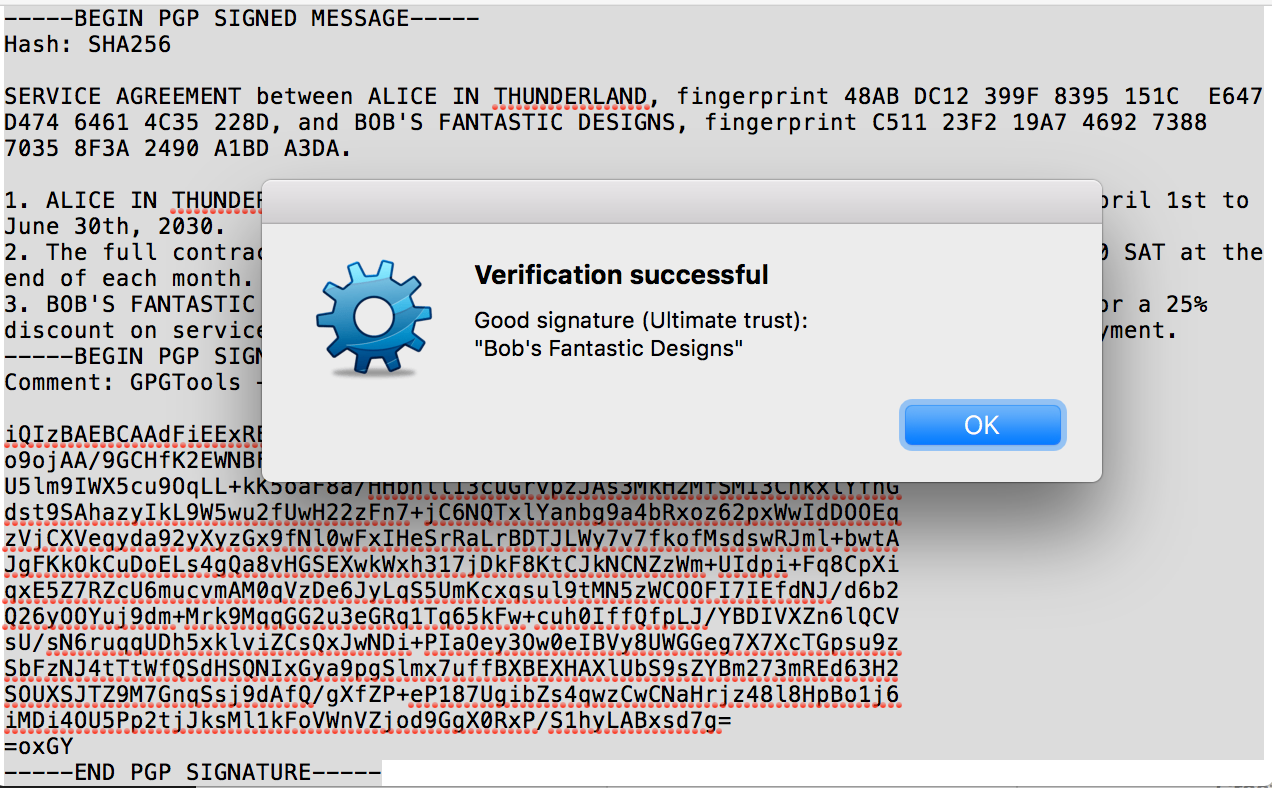

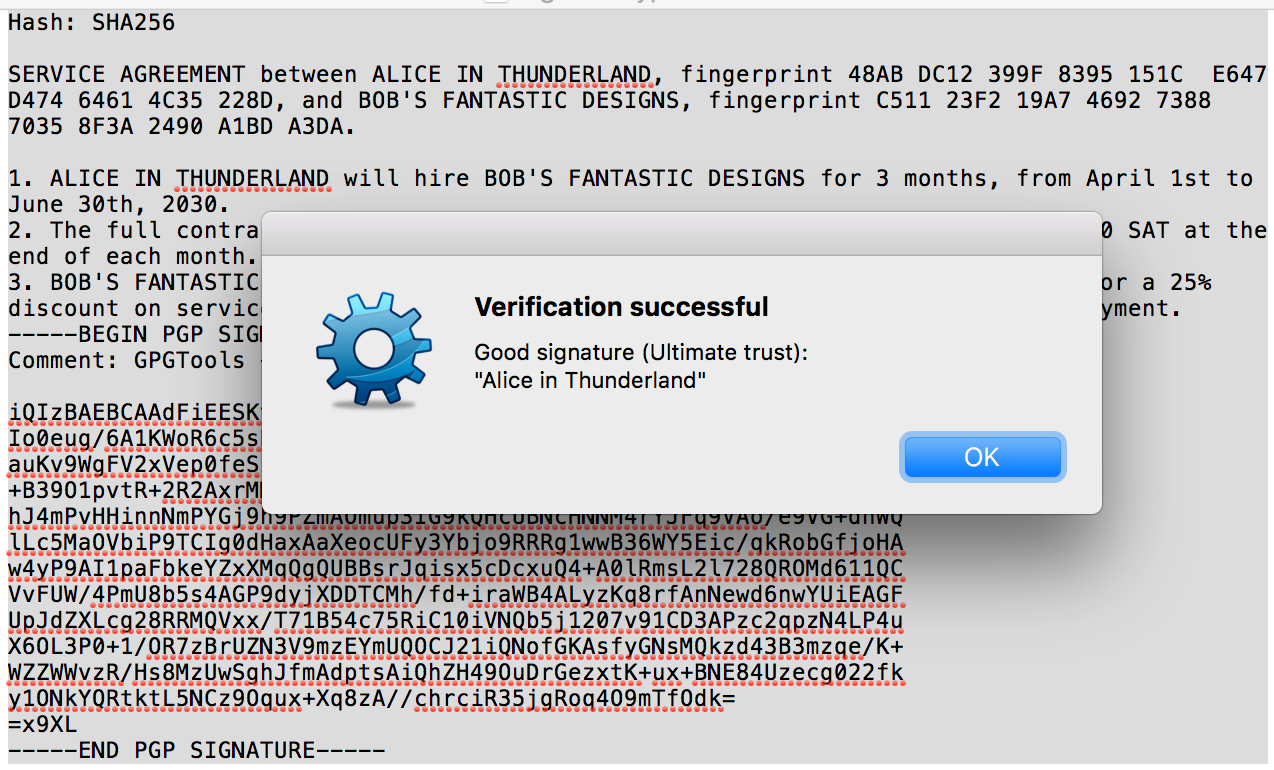

Then, Bob proceeds to sign the contract with his PGP key.

It is now Alice's turn. She verifies the hash and signs the contract, too.

Being prudent, Alice and Bob use their PGP software to verify that it was indeed the intended counterparty who signed the contract, and not someone else. Gladly, the power of cryptography makes such signatures unforgeable.

We now have a cryptographic contract with verified signatures. Unless Alice's or Bob's identity was compromised (their private key stolen), they cannot claim, "It was not me!"

Timestamping

The second step is to make sure that both parties know when the contract was signed. There may arise situations in which knowing the date and time of entering into agreement is important. In my opinion, each contract and any amendment to it must be timestamped, especially now that we have the best time-machine available to us—the bitcoin blockchain.

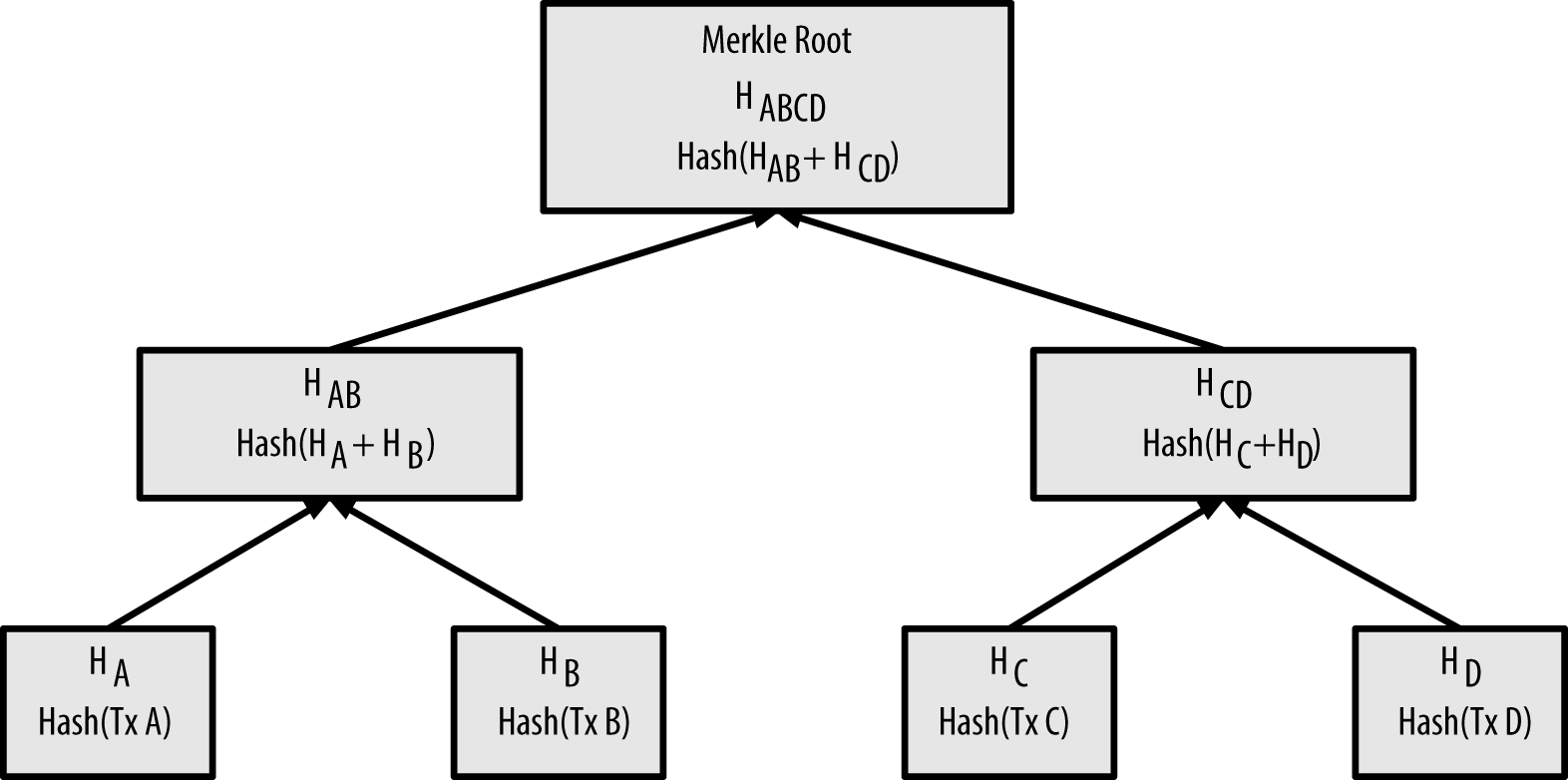

OpenTimestamps is a protocol designed specifically for this purpose. With it, you can prove that certain data existed at a particular point in time. Moreover, it does not matter how much data. You can prove the existence of the whole Alexandria library to the letter, if only you had a hash calculated from its contents.

Alice timesatmps her contract by issuing an OpenTimestamps command:

> ots stamp contract-signed_by_alice.txt

This action generates a file in the same folder with the .ots extension (in Alice's case, contract-signed_by_alice.txt.ots). The file contains the hash of the contract text with the cryptographic signature (different from the hash of just the text) and is submitted to OpenTimestamps servers. There, it will be included in the next batch of data that will be timestamped forever on the bitcoin blockchain.

Submitting to remote calendar https://a.pool.opentimestamps.org

Submitting to remote calendar https://b.pool.opentimestamps.org

Submitting to remote calendar https://a.pool.eternitywall.com

Follow the link below for an in-depth explanation of how the protocol works.

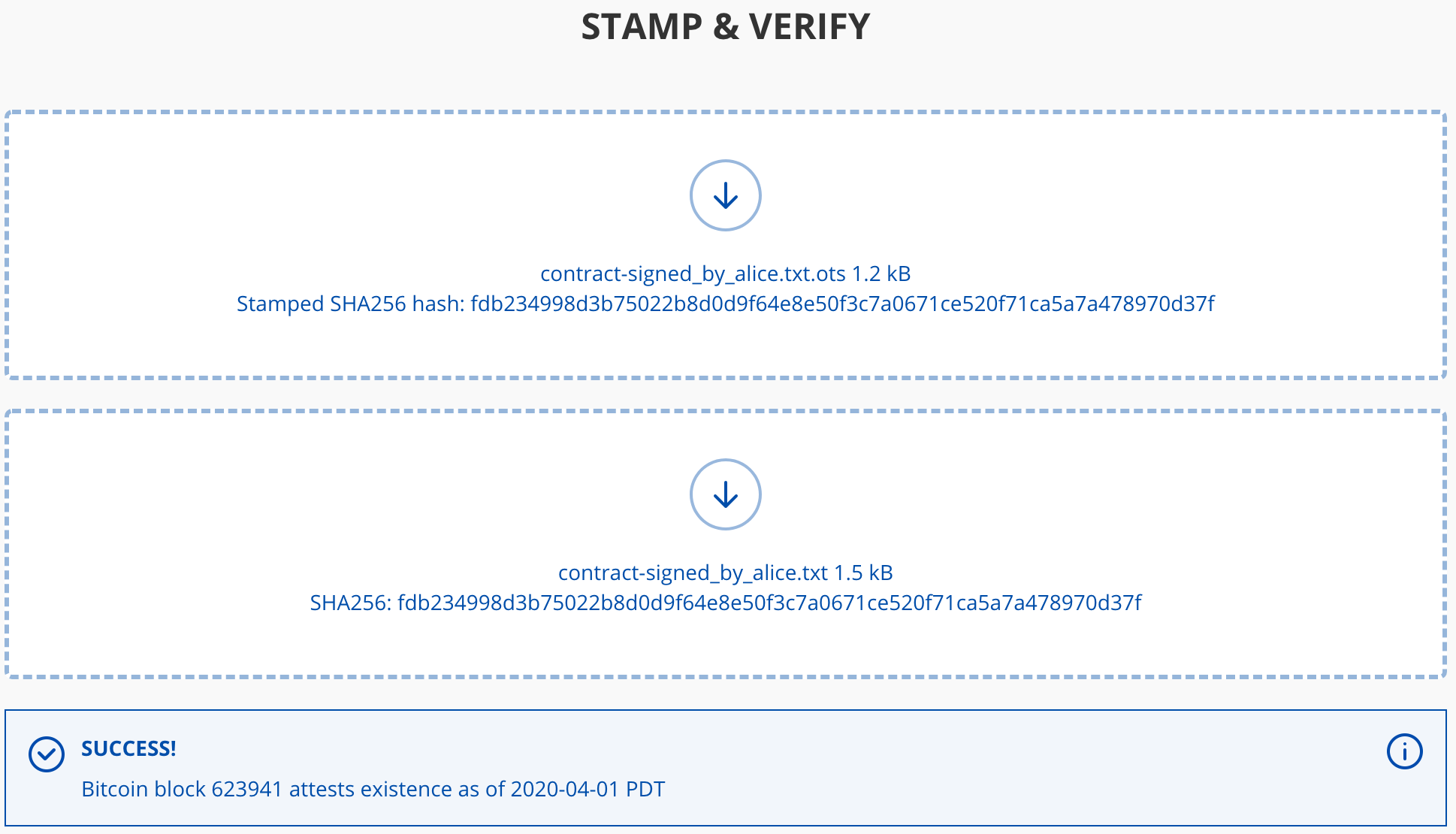

After Alice's contract has been submitted and confirmed on the blockchain, Bob can verify the timestamp using the contract file and the .ots file.

> ots verify contract-signed_by_alice.txt.ots

Success! Timestamp complete

Alternatively, the official OpenTimestamps website provides a browser-based tool for stamping and verification.

Respectively, Bob timestamps his signed contract, and Alice verifies it in the same manner.

Result

As a result, we have an agreement between Alice and Bob that is

- signed cryptographically with PGP, and

- timestamped immutably on the bitcoin blockchain!

No human intermediary needed.

Conclusion

Cryptographic contracts already exist and can be used here and now. As you can see, however, the procedures are quite complicated for non-savvy users. After all, Alice and Bob want to focus on their business and not on learning the workings of PGP and timestamping protocols.

PGP is considered the most popular tool for end-to-end encryption in email. That said, how many people do you know who use it on a regular basis? Let me guess: very few or none at all.

The reason why such extremely useful and empowering software is not ubiquitous is because of its poor user experience. Bad UX and masses are not compatible, unless it is forced upon them (think government services). Even bitcoin, in its early days, was quite esoteric for the average person to use. Today, after years of improvements in UX, it still has a long way to go but is already better suitable for use by a broader population.

I predict that the 2020s will be the decade of massive improvement in the UX of major open-source tools. Encryption software, digital identities, bitcoin, personal cloud computing, mesh networking are poised to increase their presence in our day-to-day lives. When it becomes as easy to create a cryptographic contract as sending an email, we are off to the races.

At the end of the day, this progress depends on you and me. Applied cryptoanarchy is all about the practical applications of our liberty-fuelled theories. And practice means action. If there is a good time to act, it is now.

Tinker, experiment, build.

Act.